Welcome to 2025. Self-driving cars have become mainstream. Artificial intelligence is diagnosing diseases, doing our taxes, and evaluating insurance claims. Humans are certainly also involved in these tasks, but their workload is getting lighter and more efficient.

While the world around us looks perceivably different, one thing is familiar: A new graduating college class is preparing to enter the workforce.

Today they are teenagers, mostly 14, and they, like most teens have vague thoughts about what their careers will look like in that seemingly far-off future. Ashley Voisin wants to be a psychologist, and Alexa Shelton is thinking about interior design. Reed Burzynski is considering accounting. Derek Zhang thinks maybe he’ll design spaceships.

They are all going into a workforce that experts say will be shedding jobs to machines for decades to come, but right now their more immediate concern is starting high school this fall.

Today, adults are arguing over whether robots, AI, and smarter machines will destroy more human jobs than they create, leading to worrisome headlines like a Mother Jones column that declares an era of “mass unemployment” will start around 2025. While such dire ideas are up for debate–research organizations like Forrester, Gartner, and Pew have offered varied (and often contradictory) predictions tied to 2025–rarely do we hear from those who may inherit this world.

Related: These Will Be The Top Jobs In 2025 (And The Skills You’ll Need To Get Them)

Talk to teenagers, and you’ll learn they hold nuanced and often cautiously optimistic opinions about the future of their careers, as Fast Company learned interviewing seven incoming high school freshmen and their parents this summer.

Meet The Class Of 2025

“AI, once fully developed, may allow growth in many more fields as more things can be done better by machines,” says New York City entering high school freshman Derek Zhang, who is interested in both biology and aeronautics engineering–maybe a combination of both, especially as the private space industry expands. Whether he ends up “designing space station hulls using 3D modeling software or literally decoding more about what certain genes do,” he thinks advancements in computing will be help enable what he wants to do, not put him out of a job.

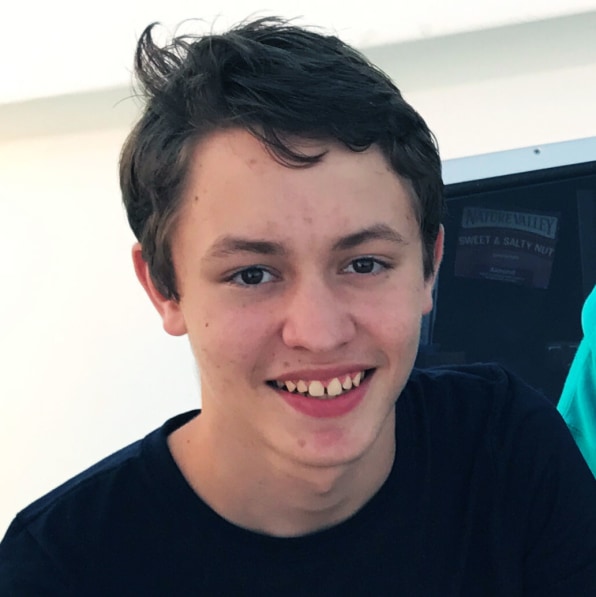

Livingston, New Jersey summer camp counselor Griffith Werwa, 14, is less certain about his career interests, but also isn’t too worried about whether there will be jobs for him when he graduates. “I feel like people will always adapt to new technology. You have to adapt to it, because you can’t really stop it,” he says. Though he’s interested in science, his plans for high school are exactly how vague you’d expect from a 14-year-old: “having a good time and getting good grades and learning something I can actually apply to the real world.”

William, a teenager entering public high school in Portola Valley, California, surrounded by kids whose parents work in the tech industry, doesn’t feel inclined to go into tech or learn coding. He’s a rare teenager who chooses to stay off social media because he “doesn’t want his data sold,” and he is wary of companies like Google and Facebook. (His parents asked that we not use his last name because of privacy concerns.)

“Eventually AI will get smarter than humans,” he says. William worries what the repercussions of that could be, and referenced Dave Eggers’ The Circle as an example for how tech could get out of hand.

Lessons In Change From Gen X Parents

Parents tend to have more immediate anxieties for their kids’ future. They have grappled with the rise of the internet, social media, and other digital technologies that have shaped their own careers, and they know their kids will likely face even less straightforward paths. But parents, too, can see the clear upside of technology and feel that the next generation will have new opportunities, too.

“Each generation has got its own challenge: Is [AI and automation] any bigger? The internet didn’t exist when I was growing up. Now it’s hard for me to imagine a life without it,” says Derek’s mom, Yan Zheng. Her career as an environmental research scientist has taken unexpected turns, made possible by a more globalized online world, she says. Recently, for example, she moved to China to teach at a new university, while Derek stays in New York with his father to start high school.

Related: What Will Work Look Like In 2025

Griffith’s notion of adaptability is also one taken from his father, Todd Werwa, who started his own career in sports video production by lugging huge rigs and physically cutting tape. He had to quickly pick up new skills or get left behind as the industry made an abrupt transition to digital production in the 1990s. Today, Todd says, younger producers do it all: “shoot their own stuff, edit, have a YouTube channel, a podcast, and Instagram.” He feels like a dinosaur.

Of course, individuals are often resilient–especially when they grow up in middle- or upper-middle-class families, which applies to those interviewed for this article. Whether the economy as a whole will adapt to more automation, especially in lower-paid jobs like cashiers and truck drivers, is the bigger dispute among experts. Most agree that many existing jobs will eventually be lost to or significantly marginalized by machines, but they divide over whether new and better jobs will be created to replace those that are lost.

Griffith’s dad is currently a coordinating producer for MLB Network. He has seen this debate in his own industry, in the discussion over whether computers should call Major League Baseball games, rather than (or along with) unionized professionals: “When computers can tell instantly whether a ball is in the strike zone, is there a need for umpires?” Werwa asks.

Griffith says that we need to think about the implications of these kinds of questions now. “I think AI has the potential to be a very good thing, as long as it’s kept in check, as long as we don’t allow it to take over everything and to take over every possible job.”

“You Be You”

Parents, educators, and students are all aware that new modes of learning will be necessary for kids to compete and work within a more automated economy. The Class of 2025 has the next eight years to develop important skills.

“A lot of the focus of our schools is getting people to sit quietly and follow instructions, and I think that doesn’t work going forward,” says Erik Brynjolfsson, director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy.

Careers of the future, he believes, will require that people either learn to build and program machines or take on creative, interpersonal, and emotional tasks that computers still aren’t good at. People should also strive to be experts at something, so finding something to be passionate about is important: “Really being a little above average or average doesn’t get you a whole lot,” Brynjolfsson says.

Related: 7 Skills Managers Will Need In 2025

Many schools are working to adapt to some of these ideals–emphasizing technology and career education, entrepreneurial skills like social media and personal branding, project-based classroom learning over memorizing facts and holding lectures–but change is slow.

“A good teacher helps them think critically about what’s going on. The tools and resources that help them reach conclusions are becoming so much easier to access,” says Austin, Texas middle school teacher Charlie Applegate, who teaches an unusual class called “Tinkering.” “I think schools need to get away from rote learning.”

Parents and teenagers seem to understand this advice intuitively and know a lot of it may fall to their own initiative. Ericka Burzynski, a medical writer in Milwaukee, encourages her ninth-grade son Reed to practice talking to adults and holding conversations, because many of his peers have difficulty with this skill, she says, especially because of smartphones. “They don’t have the skill that they are going to need to land a job and maybe to keep a job.” She only allowed him to have a device this year, much later than most of his friends.

Related: 4 Ways Your Office May Change By 2025

Ninth graders are also taking the task of finding their passions into their own hands. Alexa Shelton, 14, who has an interest in interior design, likes to frequently rearrange and redecorate her room, which her parents allow. She follows brands like Pottery Barn and Anthropologie on Instagram for inspiration.

“We encourage her to follow her dreams,” says her mom, Jennifer Gordon, who works as an associate director for a pharmaceutical company in Virginia. “We always do ‘you be you’ in our household.”

An extreme example of this is Calgary, Alberta teenager Ashley Voisin, who has been homeschooled along with her younger sister for the last two years. Their parents felt their kids’ independent streak was being stifled in traditional classrooms.

Their mom, Jacqueline Voisin, 40, who owns a home building and renovation business with her husband, is involved in directing their education to meet graduation requirements, but gives them as much time as possible to independently explore. Together, the sisters enter local Maker Faires, have launched a company called RobotsRFun that sells DIY technology kits (Ashley is the social media and design director), and visit local businesses and research institutions to learn hands-on from mentors. Ashley, who is interested in psychology as a career, also takes online college courses through the edX platform.

“I think that schools should be based off of project learning. When you work on something that isn’t a test–you are still going to get marked on it, but you’re not going to get ‘this is wrong this is right,’ which is like the real world,” Ashley says.

Clearly not everyone has parents who are so involved in their kids’ education and lives. Jobs are expected to change in all industries and at both ends of the income spectrum, but the consequences for low-wage workers–especially those in the service sector economy–in the Class of 2025 are going to be greater.

Related: 5 Jobs That Will Be The Hardest To Fill in 2025

“We as a society are ill-prepared for what’s to come. I think we’re going to see a rather dramatic shift in the economy sometime within the next generation,” says Steve Smith, communications director for the California Federation of Labor, an umbrella organization of 1,200 unions.

“We talk to young folks all the time who say I’m working two or three jobs and I have a college degree, and none of those things are what I set out to do. It is going to accelerate in that direction unless we make some big changes.”

Parents do have a general sense that, while their kids will have more options to follow their passions and excel in unusual and creative careers, it will also be more competitive. “It’s getting harder to get ahead and do well. There’s so much more competition,” says William’s mother Tricia.

Kids also say it will fall to their generation to make sure technology is used as a force for good.

“I think that we’ll definitely have a more comfortable life in terms of ‘having things’ and ‘owning things.’ But life is also getting more complex,” says Ashley Voisin. “If we want to live in a happy and stable world, then we have to work together to build it. We can’t just hope for it and wait for it to happen.”

Comments are closed.